Sometimes my own head is a cruddy place to be.

Sometimes my own head is a cruddy place to be.

It’s noisy, for one thing. And really very—close. Like a hall of mirrors all parroting my least appealing inner voices back at me. (Let’s just say they aren’t all waving little “Yay” flags and singing “THIS GIRL IS ON FIYYY-RRREEE.)

I mean, it’s not like that all the time, but when it is, or when I really need some serious distraction, there’s no better cure for being too much all in my headthan the chance to spend a little time in someone else’s, particularly if that someone else has managed to make some kind of sense of why we’re all basically so caught up in our own inner dialogues that it’s hard to hear anything else.

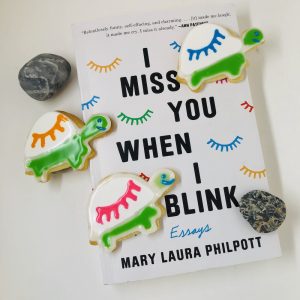

If you’re in that place, I present you with Mary Laura Philpott’s I Miss You When I Blink.

Mary Laura also wrote this: Hard Knock Life: What Are the Turtles Telling Me?

Which is why I, when faced with the unexpected appearance of a turtle cookie cutter on a day when I really wanted to buy a cookie cutter, purchased it, used it as it was intended and presented her with celebratory book cookies. (She is a friend, but I would not tell you to buy her book on that account. If I didn’t like it I would maintain a discreet silence, although if you have written a book and I did not say anything about it that does not necessarily mean I didn’t like it, it could also mean it was published on the day my kid broke her arm, or that I’m too jealous to speak, or any of a variety of things.)

I love decorating cookies, enough so that I once considered it as a career before concluding that there would be no faster way to stop loving decorating cookies (that may be true of a lot of things). And this turned out to be the first time in sixteen years that I was able to get everything all in order the way I like it (all cookies made, all colors made and placed in appropriate vessels for piping or flooding, decks cleared, time and space planned) to sit down and really savor playing with icing and color without a lot of “help”.

It was glorious.

I think I’m supposed to say it was also a little sad, because my little cookie-decorating monsters are all big now, but it wasn’t. It was great. And when I was done, I let my teenagers loose on the remaining cookies and frosting and they had a lovely time, and we didn’t even end up with sprinkles in anyone’s hair, and then they (the cookies, not the teenagers) all got eaten (can I just say SOMEONE IN THIS HOUSE KEEPS EATING TURTLE HEADS AND IT IS CREEPY).

That wasn’t particularly profound, but if you’re looking for something to read, it is helpful.

On the other hand, Madeline L’Engle’s  A Circle of Quiet is not an opportunity to getout of your own head, and the glimpses she offers into hers are (for me at least) of the “don’t make friends with the rock stars” variety.

A Circle of Quiet is not an opportunity to getout of your own head, and the glimpses she offers into hers are (for me at least) of the “don’t make friends with the rock stars” variety.

It’s described as the first in a series of “journals” she wrote at her family’s country home. This isn’t really her journal, though–it was clearly written for publication. I treasured about the first two-thirds, especially her memories of fitting in writing around household work in the days before she was published, and then after, and her musings on the “terrible times” she lived in, when older people were destroying the world and young people could not stand silence and had to fill it with “their transistors” (the book was first published in 1972). #historicalperspective duly noted.

But as I read on, I realized there’s a reason I hadn’t heard of this, in spite of being a fan of her novels for years.

It’s—snobby.

I had a lot of other words in my head, but that’s the only one I can settle on. As L’Engle began to spend more and more pages describing the way writers and artists live in a world apart, and “the common man” stays in some safe, distant place, far away from the influence of art, fearful of its impact and trying to protect his children from fairy tales and big thoughts and even bigger dreams, I felt a gulf opening between her as writer and me as reader. I suspected that she thought me a bit common, possibly capable of more, since I was reading her words, but probably not, and certainly not unless I agreed with her wholeheartedly and also let her lecture me for a few more chapters.

That’s not what I came in for.

I think it’s possible that I’m not getting out of it what she intended, and that it’s harder to read than a modern memoir, and that L’Engle did not want to connect through this piece of writing, but rather to say some things about her times and her work and how she thought it fit into those times. Amazon reviewers seem to like it–but do they like it because they like it, or because they like her?

It’s also possible that this particular great novelist was not as skilled in other genres. I’m going with that. (If you thought differently, reply to this email–I’d love to hear about it.)